The Journey of AI from Virtual to Physical Realms: Bringing ChatGPT to Life

A company founded by three former OpenAI researchers is building A.I. technology that can navigate real-world environments using the techniques behind chatbots.

The Journey of AI from Virtual to Physical Realms: In the digital world, companies like OpenAI and Midjourney are developing chatbots, image generators, and other artificial intelligence tools.

A company founded by three former OpenAI researchers is building A.I. technology that can navigate real-world environments using the techniques behind chatbots.

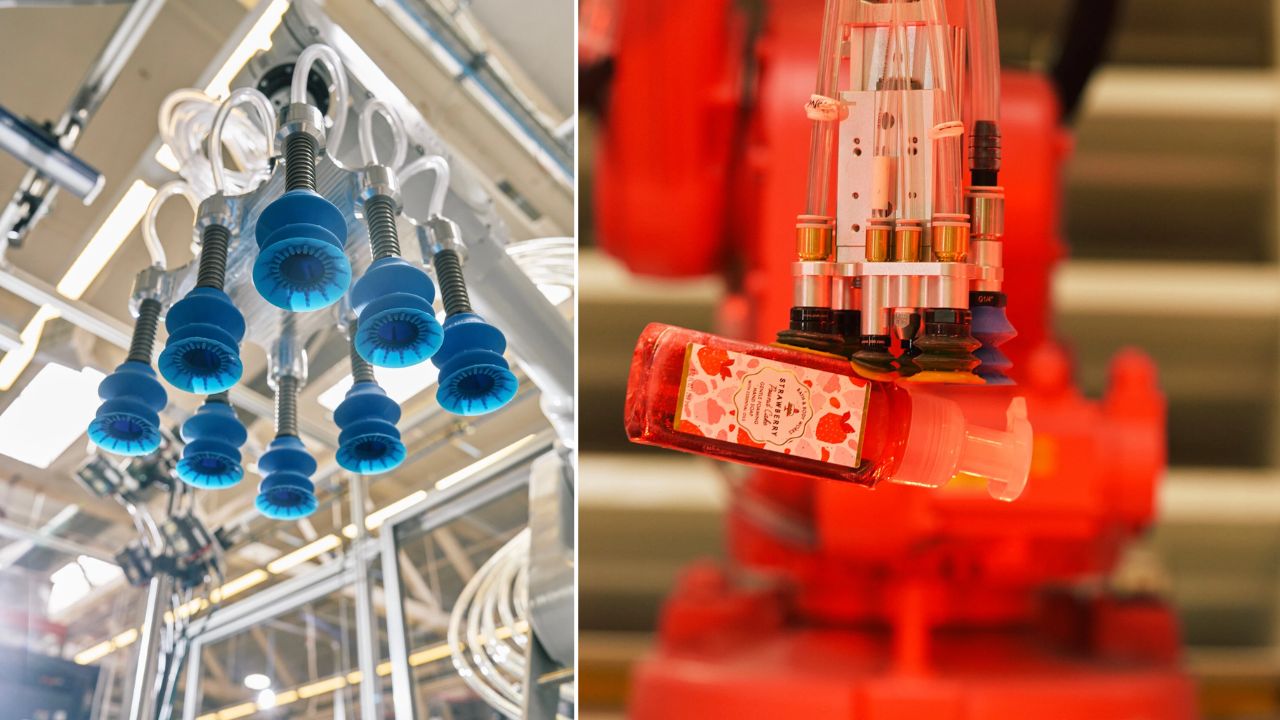

Robots are being created by Covariant, a robotics company based in Emeryville, Calif., to pick up, move and sort items as they move through warehouses and distribution centers. By doing so, robots will be able to determine what to do next based on what they are seeing and hearing around them.

It also gives robots a broad understanding of the English language, allowing people to communicate with them as if they were chatting with ChatGPT.

How will AI process in the Physical World?

Although it is still under development, this technology shows that the artificial intelligence systems that power online chatbots and image generators will also power machines in warehouses, on roadways, and in homes.

Engineers can improve this robotics technology by feeding it more and more digital data, just like chatbots and image generators.

In spite of $222 million in funding, Covariant does not manufacture robots. Instead, it develops software for robots. By deploying its new technology with warehouse robots, the company hopes to inspire others to follow suit in manufacturing plants and perhaps even on the roads with driverless cars in the future.

Artificial intelligence systems that drive chatbots and image generators are called neural networks.

Using patterns found in vast amounts of data, these systems can recognize words, sounds and images — or even generate them for themselves. This is how OpenAI built ChatGPT, which can instantly answer questions, write term papers and write computer programs. These skills were learned from text culled from the internet. (Several media outlets, including The New York Times, have sued OpenAI for copyright infringement.)

It has become increasingly common for companies to build systems that can analyze different kinds of data at the same time. An algorithm can learn that the word “banana” describes a curved yellow fruit by analyzing both a collection of photos and captions for those photos, for example.

An automated warehouse system built by Covariant, founded by Pieter Abbeel, a professor at University of California, Berkeley, and three of his former students, Peter Chen, Rocky Duan, and Tianhao Zhang, uses similar techniques.

It has spent years collecting data – from cameras and other sensors – that shows how sorting robots work in warehouses around the world.

“It ingests all kinds of data that matter to robots — that can help them understand the physical world and interact with it,” Dr. Chen said.

The company builds A.I. technology that gives its robots a much broader understanding of the world around them by combining that data with the huge amounts of text used to train chatbots like ChatGPT. Robots can handle unexpected situations in the physical world after identifying patterns in this stew of images, sensory data, and text.

Like a chatbot, it understands plain English. If you tell it to “pick up a banana,” it knows what that means. As it tries to pick up a banana, it can create videos that predict what might happen. These videos are not useful in a warehouse, but they show the robot’s understanding of its surroundings.

“If it can predict the next frames in a video, it can pinpoint the right strategy to follow,” Dr. Abbeel said.

Though it often understands what people ask of it, there is always the possibility that it will not. It drops objects from time to time. The technology, called R.F.M., stands for robotics foundational model. Robotics foundational model makes mistakes, much like chatbots do.

“It comes down to the cost of error,” he said. “If you have a 150-pound robot that can do something harmful, that cost can be high.”

Researchers believe this kind of system will rapidly improve as companies train it on increasingly large and varied data collections.

It is very different from the way robots used to work. The engineers typically program robots to repeat the same precise motion — say, picking up a box of a certain size or attaching a rivet to a car’s rear bumper. Unexpected or random situations, however, couldn’t be handled by robots.

Researchers expect the technology to rapidly improve as companies train robots on increasingly large and varied collections of data.

Robots can learn from digital data — hundreds of thousands of examples of what happens in the physical world, coupled with language — to handle the unexpected.

As a result, robots will become more agile, like chatbots and image generators.